Grinding poverty in New Zealand is a direct result of 30 years of neoliberal policy, writes University of Auckland's Dr Ian Hyslop*

|

| pn161 |

Newsroom journalist Laura Walters’

discussion of New Zealand’s starkly unequal education system earlier this week identifies appalling gaps in the achievement levels of our school children – gaps that are inscribed within class and race divisions.

Radical and unnecessary inequality is a blight on contemporary New Zealand society. Deprivation is produced economically and experienced socially.

In Auckland, our city of sails and aspirational ‘liveability’, social workers witness the bare-floored, bare-walled reality of grinding urban poverty every day. This outcome is a direct result of 30 years of neoliberal economic policy.

Neoliberalism is an aggressive form of capitalism. We seldom refer to capitalism in mainstream political discourse which is why it was so refreshing to hear the enigmatic Winston Peters mention it in his announcement of the current Labour-led coalition Government in November 2017. Peters went on to suggest that too many New Zealanders have come to see capitalism as a foe rather than a friend and that a return to capitalism with a human face is required.

Perhaps the real nature of capitalism is something of an embarrassment to our political masters – a bit like the other problematic ‘c’ word: colonisation. Or perhaps the name of our economic system is not worth mentioning because it is uncontested; it goes without saying. We are more likely to hear about the importance of markets, investment and economic growth. However it is important to recognise that macro-economics is not an exact science. It is best understood as a set of politically contested ideas and tools for making choices about the way in which wealth and wellbeing are produced and distributed in society.

Over three decades, New Zealand and similar liberal societies have moved away from the post-war welfare state consensus. Manufacturing has shifted to parts of the world where labour is cheap. This economic transition has created serious challenges here and on a global scale. Disenfranchised rust-belt America has delivered us the bizarre and deeply disturbing Trump administration for example.

If exclusion is the engine of capitalism, give me socialism every time.

It is not as if we had not been warned about the destructive social divisions which unrestrained capitalism produces. In the preface to his 1973 book Economics and the Public Purpose, the American economist J.K. Galbraith reflected that “On no conclusion is this book more clear; left to themselves, economic forces do not work out for the best, except, perhaps, for the powerful”.

In our case it was not simply a matter of letting economic forces take their course. Our politicians obligingly kicked down the doors. Changes to industrial law seriously reduced the power of organised labour and the infamous Richardson benefit cuts of 1991 sentenced a generation of children to white bread and fizzy drinks. The underlying philosophy descends directly from the Victorian Poor Laws - that poverty is the spur of industry and self-discipline. This political and economic policy prescription has generated staggering inequality in our fair land.

The second component of neoliberal state policies has involved the subtle replacement of a sense of social responsibility with the dogma of self-responsibility. Middle class parents are increasingly obsessed with the educational progress of their children as they prepare them for a world that is understood as an individualised competitive marketplace.

The 2015 report of the Productivity Commission of New Zealand backgrounds the much talked about social investment agenda. This report also has disturbing echoes of the late 1900s: deficient classes of people can be identified and re-moralised.

Now, I am not suggesting that families and communities don’t need better social services: they most definitely do. But it is a convenient illusion to assume that poverty results from a lack of industry amongst the poor. Inequality is about macro-economic policy; how we choose to distribute wealth and opportunity.

KiwiBuild homes for families in the $80,000 to $180,000 earnings bracket will help to re-enfranchise the children of the relatively comfortable, but for far too many people in New Zealand society capitalism with a human face remains an empty promise.

It is time to re-include those whom we have systematically left behind in the tragic neoliberal experiment. If exclusion is the engine of capitalism, give me socialism every time.

*Dr Ian Hyslop is a senior lecturer in the School of Counselling, Human Services and Social Work, Faculty of Education and Social Work at the of Auckland. His professional interests are tied to a concern with the relationship between social work and social justice, locally and globally. He worked for twenty years as a social worker, supervisor, and practice manager in statutory child protection practice in Auckland, and then as a fieldwork coordinator, programme director and lecturer in the Unitec Social Practice degree programmes for eight years before joining the CHHSWK team as a lecturer in July 2013.

***

Note: Statistics NZ reported a sharp increase in household income inequality from the late 1980s to the mid 1990s, when Roger Douglas ("Rogernomics") reversed traditional Labour Party economics; then a small rise to the mid 2000s, and some increase in the last few years.

Stuff Report on Inequality

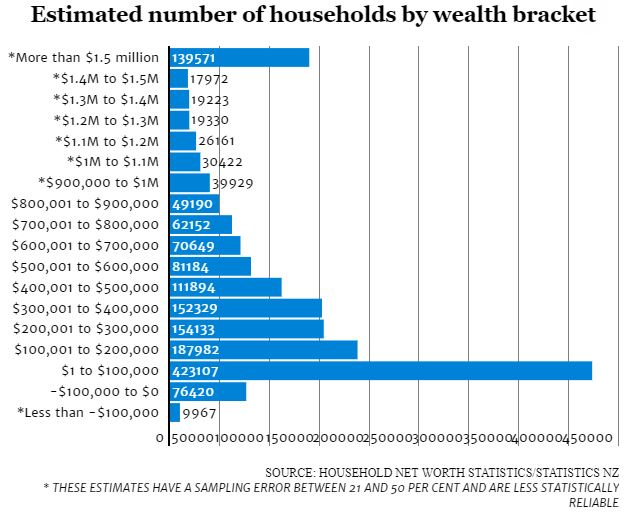

However, a Stuff report in January 2017, which included these graphs, showed that the income of the wealthiest 20% of households equalled 70% of total incomes, and the top 10% equaled one-half. Read the full article here.

Graph 1 shows two measures of income inequality (pop. ratio 80:20, and pop. ratio 90:10) from 1982-2015

Graph 2 shows income by decile.

Graph 3 shows inequality before and after housing costs.

A recent Oxfam report states that the combined wealth of two NZ billionaires is greater than that of the bottom 30% of the adult population.

I used a StatsNZ table to produce the graph below on personal incomes in 2018. There were an equal number of individuals in each decile. The blue line representing all individuals is therefore 10. Maori and Pasifika are over-represented in the lower income deciles and Europeans are over-represented in the top.

Measuring inequality by income alone obviously has serious limitations. Government has signaled that Treasury and future budgets will use measurements based on wellbeing and living standards (See Grant Robertson's speech to the Labour Party Conference, pn160). These should give us a better understanding of the "real" extent of poverty in NZ today.

--ACW

No comments:

Post a Comment