|

- This first of four posting will consider why polling is often less than accurate. Pn24

- The second will examine polling methods for preferred party and PM polls used by 1NewsColman Brunton polls in NZ and the FijiTimes/Tebbutt and the FijiSun/Razor polls in Fiji.

- The third will report on some preferred party and PM polls poll results and reflect on what some NZ and Fiji commentators have had to say about them.

- The fourth will look at some poll results in Fiji that touch on other political issues, and what commentators have deduced from them.

With the Fiji elections approaching it is timely to re-visit the value of opinion surveys. If you or your acquaintances read poll results, you should be sure about how they are conducted or the wool may be pulled over your eyes.

Polling Methodologies

There has been more

than usual debate worldwide about the accuracy of polls, most

especially following their inaccuracy in calling the US elections result. How wrong they were that Hillary Clinton would beat Donald Trump.

Polls are based on samples of a total population which are intended to reflect the opinions of the total population. Unfortunately, the methodology used to establish a truly representative sample (which is often not fully revealed by many pollsters) is often far from perfect. Today, to reduce costs -- and with some methodologies to improve accuracy -- many sample interviews are conducted by telephone. We shall consider polling methods more fully in the second posting.

Polls are based on samples of a total population which are intended to reflect the opinions of the total population. Unfortunately, the methodology used to establish a truly representative sample (which is often not fully revealed by many pollsters) is often far from perfect. Today, to reduce costs -- and with some methodologies to improve accuracy -- many sample interviews are conducted by telephone. We shall consider polling methods more fully in the second posting.

So why were the polls

less than accurate?

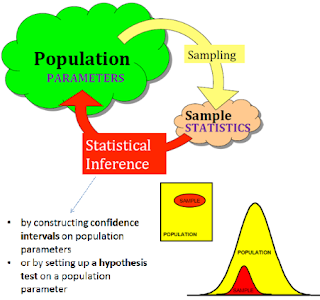

In “perfect” polls pollsters need to accurately know the size, demographic characteristics and location of the total population they are studying -- a relatively easy task in an homogeneous population but most difficult in a diverse population like Fiji -- so that they can take an accurate sample, typically one or more thousand people who are assumed to be representative of the total population. From this, pollsters can estimate the statistical “probability” of their sample conclusions being plus or minus so many percentage of the population “reality.” This approach is called inferential statistics.

In “perfect” polls pollsters need to accurately know the size, demographic characteristics and location of the total population they are studying -- a relatively easy task in an homogeneous population but most difficult in a diverse population like Fiji -- so that they can take an accurate sample, typically one or more thousand people who are assumed to be representative of the total population. From this, pollsters can estimate the statistical “probability” of their sample conclusions being plus or minus so many percentage of the population “reality.” This approach is called inferential statistics.

Given the number

of people who hang up on telephone interviews, or who grow weary and

offer any sort of answer if there are too many questions or if the interview is too long,

or who feel they are being prompted towards answers than match the

opinions of the interviewer, it is a wonder the US polls were

as accurate as they were.

Ideological and confirmation biases (respectively, when polls are looking for what we believe in, or looking for more evidence to support what we believe in) are not thought to have had much influence in the US election, and I doubt they have much influence in New Zealand. I am less certain that this is always the case in Fiji. My Fiji research (“Ethnicity, Gender and Survey Biases in Fiji”, The Journal of Pacific Studies, 19 (1) 1995:145-157) showed responses on sensitive issues significantly differed when the ethnicity and gender of interviewers and those interviewed differed.

Ideological and confirmation biases (respectively, when polls are looking for what we believe in, or looking for more evidence to support what we believe in) are not thought to have had much influence in the US election, and I doubt they have much influence in New Zealand. I am less certain that this is always the case in Fiji. My Fiji research (“Ethnicity, Gender and Survey Biases in Fiji”, The Journal of Pacific Studies, 19 (1) 1995:145-157) showed responses on sensitive issues significantly differed when the ethnicity and gender of interviewers and those interviewed differed.

So why use telephone

polling?

Because it is the most cost efficient polling method. The

costs of face-to-face household interviews are beyond

the budget of most pollsters, and face-to-face interviews possibly have bigger problems of interviewer and subject bias (the biases of

the interviewer, and the perception that those interviewed hold of the interviewer) which is especially important, for example, when

ethnicity or class of the interviewer is very different from those

interviewed.

Of course, the number

of households that own telephones from which the sample population is

drawn has always produced a sample bias in favour of the urban,

middle class. But today fewer people, even in in urban areas and

among the middle class, use landline telephones and, if America is

anything to go on, fewer people are fully responding to telephone

polls. Up to 36% in recent polls (up from an earlier 9%) do not

fully respond in telephone polling.

Some are not at home or

do not answer the phone; others hang up during the interview and an

unknown number grow weary of the questions and do not answer with

care.

It has therefore become

increasingly difficult with fewer landline phones and poorer responses to

establish an accurate sample size from which reliable conclusions can

be drawn.

The methods used by pollsters to compensate for these missing people who should be part of their sample are at the best informed guesstimates, and probably, statistically-speaking, often not very statistically reliable.

Hence, for the most part, the inaccuracy of many polls.

The methods used by pollsters to compensate for these missing people who should be part of their sample are at the best informed guesstimates, and probably, statistically-speaking, often not very statistically reliable.

Hence, for the most part, the inaccuracy of many polls.

Internet and Predictive polling

Internet polling using mobile phones, or a mix of landline and mobile phones, would be cheaper than telephone polling but establishing a

“population” and sample size would be no less difficult.

Predictive polling (who do you think will win the next

election if it was held this week?) is thought to be more accurate

than asking people who they will vote for.

The Use of Polls

Despite their limitations, political polls still have their uses because they are invaluable in getting some sense of popular thoughts on a range of issues, although I'm not aware of any research showing the effect of political polls on actual voting behaviour.

In considering poll findings, we should always consider the political context within which they are held and used, and the possible political motivations of their publishers.

We should be informed and wary of their methodologies

We should insist on disclosures of the numbers not sampled and publication of their margins of error, with a clear indication of which results are are statistically significant -- and which are not.

And we should not place too much weight on one poll result. Several polls over several weeks are likely to be more accurate.

In considering poll findings, we should always consider the political context within which they are held and used, and the possible political motivations of their publishers.

We should be informed and wary of their methodologies

We should insist on disclosures of the numbers not sampled and publication of their margins of error, with a clear indication of which results are are statistically significant -- and which are not.

And we should not place too much weight on one poll result. Several polls over several weeks are likely to be more accurate.

No comments:

Post a Comment